Okay, so it’s just a small chunk of a larger project that I’ve been messing about with for fun, but still, it’s nice to see work head out into the world.

A while ago, I started taking the chess games I was playing in the club and on chess.com and feeding them into SCID-vs-PC to run analysis engines on them; and because I’m a bit of a luddite in some ways, I wanted to be able to print off a report on them so I could sit down at the table with a cup of tea and a chessboard and play through a game while reading the engine’s analysis of it. If you don’t play chess yourself, the reason you’d do this is so you can see what moves and sequences of moves the computer thinks you should have played, and whether or not they were good lines for a human player to take – if the computer is saying “Oh, if you just played this sequence of seventeen moves perfectly you could have gained a half-pawn advantage here”, then you can pretty much ignore it unless you’ve been playing for decades and could actually do that in a game under time pressure (hint: I can’t 😀 ). On the other hand, if it says “Yeah, if you’d made this move, you’d have had checkmate in one move”, you probably want to see that so you remember the tactic in case you ever see it again 😀

Now SCID-vs-PC couldn’t print directly itself but it had a LaTeX report output function so I tried that, and found it relied on a LaTeX package called chess12 which was for LaTeX 2.09, even though LaTeX2e replaced Latex 2.09 in 1994 and chess12 itself hadn’t been touched since 1992. Turns out to be quite hard to get that old a setup to work, so effectively the LaTeX output was useless. But SCID-vs-PC is an open source project in a language I’ve been working in for decades and I did more than my fair share of LaTeX writing in college and afterwards (academia uses LaTeX pretty extensively because only a masochistic sociopath would entrust their thesis or research papers to Microsoft Word), so I figured it couldn’t be too hard to fix. And it wasn’t – I was able to get it to use a newer LaTeX chess package called skak, and to add in some nice graphing using ps-tricks as well as formatting things better on an A4 page using koma (all of which are standard LaTeX packages for all the sane distributions out there). But it has seriously renewed my belief that C++ is not a great language to do string processing in 😀

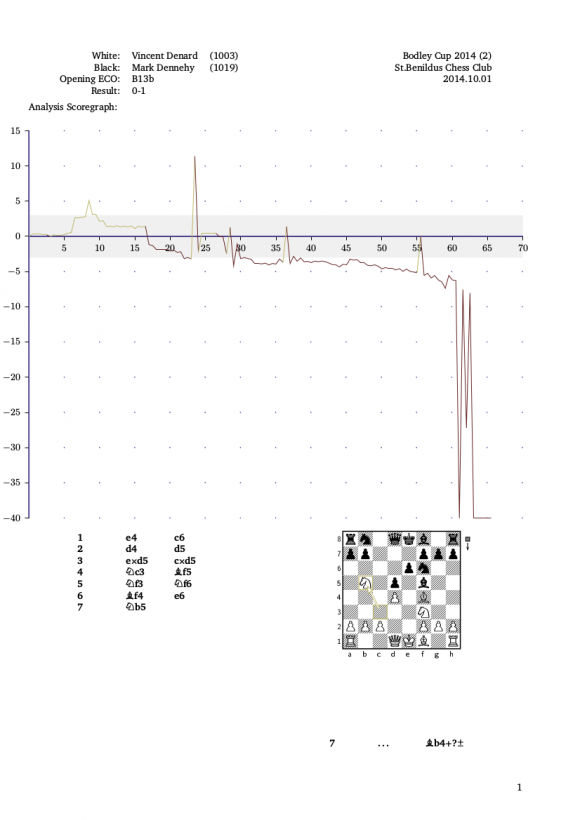

Anyway, the first version of the report code just shipped in the latest SCID-vs-PC version (4.13). I still have a few more ideas to bolt in there, particularly around the analysis graph and the detection of analysis scores in the PGN files (which seem to have different formats from just about every possible engine). And we already have some pretty serious refactoring in mind because the code’s a bit of a mess when it comes to output. But for now, if you load your game up in SCID-vs-PC and spit it out in LaTeX format, then run it through the standard latex-dvips-pstopdf chain (for some reason the latex2pdf tool chokes at the moment, that’s on the list of things to fix), you’ll get something like this: